Ron Jackson

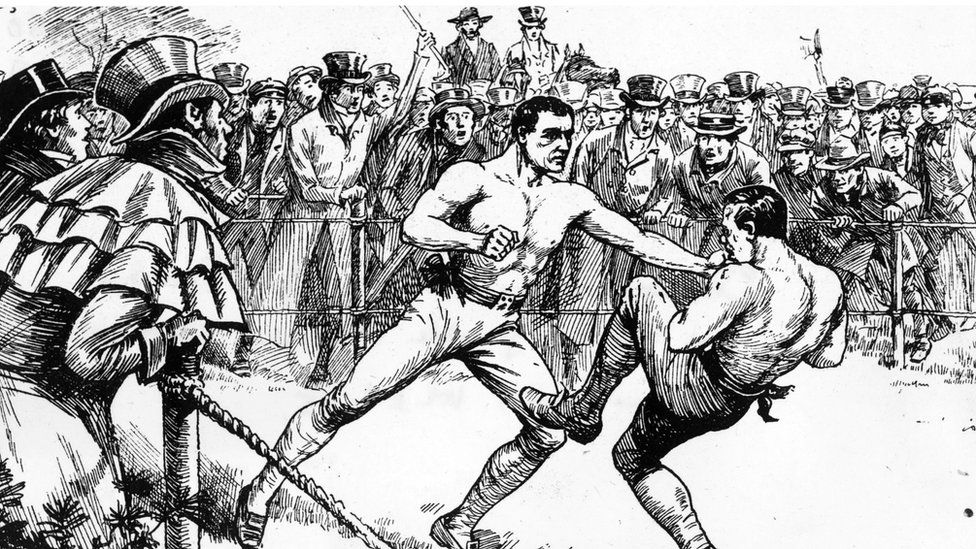

Boxing, still seen by many critics as a brutal sport that should be outlawed, has come a long way since the days when men fought bare-fisted in blazing sunlight or pouring rain.

The earliest records of boxing date from before the days of the Greek and Roman Empires.

Egyptian hieroglyphics from around 4 000 BC indicate that some sort of fighting took place between soldiers.

Bare knuckle fighting was one of the first organised sports yet is was illogical that it was considered illegal in the eyes of the law.

There was also tremendous pressure by politicians and religious leaders to have the sport banned.

During the heyday of prize-fighting, as it was then called, venues were often natural amphitheatres in which almost every spectator had a good view.

The ring was 24 square feet and was surrounded by an outer ring in which only the two umpires, the timekeeper, the backers and a few favoured friends were allowed.

Also stationed in the outer ring, were “whippers-out”, whose job was to keep the crowd from encroaching.

Occasionally, a stage was used with turf spread upon the boards, which made it an awkward surface to fight on. Turf on solid ground was the norm those days and a better surface. For such fights the boxers could wear spiked shoes.

Every fighter was entitled to one second and one bottle holder. Stools were not used. A fighter would sit on his second’s knee, listening to instructions while the bottle holder sponged him down and wiped away any bleeding.

Sometimes the fighters took terrible punishment and the seconds resorted to drastic action to bring their fighters around. Frequently they bit a fighter’s ears or lanced the swelling beneath a man’s eye to prevent him from being unable to see his opponent.

Each fighter had his own colours and tied his scarf to the ring post in his corner.

All fights had to continue until one boxer gave in or could not come out (“come to scratch”) within a specified time. In terms of the Broughton Rules the “scratch” was “the square of a yard” in the middle of the ring.

A round would end only when both or one man went down from a blow or a throw. Intervals were 30 seconds and after time was called, the combatants were given eight seconds to reach the “scratch”.

In early fights the seconds carried badly beaten fighters to the scratch, but this was later changed and fighters were required to reach the scratch unaided.

Fighters suffered far more damage than in gloved contests and knock-out blows were uncommon because a round ended when a fighter went down. He then had 30 seconds to recover, plus the eight seconds to come to scratch.

Bare-fisted blows on hard bone caused the knuckles to swell and at times fighters were in agony every time they landed a blow. For this reason fighters pickled their hands in brine or some astringent before a fight.

Most fights were outdoors, so there were also natural conditions to contend with. Some fighters tried to manoeuvre their opponent so that the sunlight was in his eyes. Rain would handicap an agile man on grass or a slippery stage. They also had to contend with cold weather at times.

When the fight was over, the boxers often had had be taken away and put to bed to recover from the punishment.

There were also times when it became a bad business riddled with fraud and deception, because of the big bets placed on the fights.

Because of the severe punishment, bare-knuckled fighters participated in far fewer fights than modern boxers.

However, despite the brutality of these fights there were few deaths in the ring.

The last bare-knuckle fight for the world heavyweight championship was between Jake Kilrain and John L Sullivan, won by Sullivan after 75 rounds, on in 1889 in Richburg, Mississippi.

Two of the longest bare-knuckle fights to take place in South Africa both involved Barney Malone.

On late 1889 Malone beat Jan Silberbauer when, after 212 rounds and five-and-a-half-hours, Silberbauer was unable to continue.

The fight took place just over the Free State border, with the Cape and Bechuanaland Police looking on from their own territories.

Four years later, Malone met Jim Holloway in a bout billed as being for the South African lightweight title on a farm off the old Kimberly road, some eight miles (13 kilometres) from the centre of Johannesburg.

Also fighting under the London Prize Ring rules, the fight lasted five-and-a-half-hours and, 73 rounds later, was called a draw.